Florence

I always tell people I’m really glad I did Florence after Rome, not the other way around. I think most people go to Rome with a lot of intention—the city has so much monumental history that you feel like you have to check everything off. Florence is different. Not in a bad way, but it’s a little less intense, and for me that was such a relief. After the relentless energy of Rome, I loved that Florence gave me some room to breathe. The views are gorgeous, the religious history is everywhere, the shopping is amazing, and of course, the food is unbelievable. I only had two nights there, so I barely scratched the surface, but it was just enough to want to go back, only this time, for much longer.

My three days in Florence were spent in hostels. In Rome, I had spent two individual nights in, but that was the extent of my experience. Before leaving for Europe, the whole idea of sharing communal spaces with strangers honestly made me nervous. But once I got there, I was surprisingly excited to meet new people and swap stories. This hostel actually had a pool (this was shocking to my parents), and it was there that I met two English girls who were passing through on their way down from Venice. Before that, they had been in Croatia, a country I have now been thoroughly convinced I need to visit. Other people were arriving from the south of France, or heading north from Rome. It was fun to compare notes with people who had been to the same places as me, but also to share my own recommendations for cities they hadn’t explored yet. I felt very worldly.

My first night, Connie and Katie (the English) and I took the tram to Piazza della Signoria, the city’s most recognizable center square. Overlooked by the Palazzo Vecchio, it’s filled with replicas of famous Florentine statues, including Michelangelo’s David. I actually found this quite disorienting and bizarre, but plenty of people seemed fascinated and were taking lots of photos. Since I knew I’d be seeing the real David the next day, I didn’t linger. However, enjoying our pizza and gelato during sunset was very serene. The girls and I simply engaged in some harmless people-watching while we enjoyed our food, and it turned into a very pleasant evening. On our way back to the hostel, we of course walked through the Piazza del Duomo to see the breathtaking Santa Maria del Fiore Cathedral. The Duomo is an architectural feat, and watching the Florentine sun sink behind its dome was stunning.

—

From a scholarly perspective, it was actually difficult to picture Florence as a neorealist backdrop. The only film I studied with scenes here was Paisan (1946), yet another picture by Roberto Rossellini (are you noticing a pattern?). Out of the six “chapters” that make up the film, only one is set in Florence, while the others move across Italy, beginning in Sicily and making their way northward. Still, Florence’s vignette carries the genre’s signature traits: stark black-and-white film, documentary-style cinematography, and an authentic engagement with wartime reality. But compared to Rome, Florence never became the movement’s cinematic heartbeat, and that’s okay, because it was something in itself to experience neorealism in a new environment.

Part of the reason Paisan tends to be overlooked in the canon is because Rosellini shot it in collaboration with a young Federico Fellini. Neorealism was one of Fellini’s many faces, though it was by no means his only one. He learned a great deal traveling around the country in the wake of World War II with Rossellini and his crew, contributing to films like this one in addition to parts of Open City. However, as Fellini came into his own career, he would find he preferred the studio, as it gave him greater control over lighting and allowed for elaborate set design. This move gave rise to the flamboyant yet sort of enigmatic style of filmmaking he’s known for. When 8 1/2 was released, I believe many film critics even said that Fellini had betrayed neorealism. That may be a bit of a stretch, though I cannot consider his early works (e.g. La Strada and Nights of Cabiria) to be authentically neorealist without some reservation.

Anyways, back to Rossellini’s Paisan, I really enjoyed this film because it reminded me of my own course through Italy. I’ve never really seen a film move in this manner and though it’s ambitious, it’s actually very clever. Mirroring the Allied invasion of the country, Rossellini encompasses the whole of Italy, stopping city-by-city, just as I had. As previously mentioned, Episode IV unfolds in Florence, a city torn apart as Nazis and partisans battle street by street. At the center is Harriet, an American nurse, and her Italian friend Massimo. Both are desperate to cross the Arno: Harriet in search of her lover, Lupo, a Resistance leader, and Massimo hoping to reunite with his wife and child. What follows is a tense, perilous journey through the divided city. By the time they finally reach the other side, Harriet discovers—almost by chance, from a dying partisan cradled in her arms—that Lupo has already been killed earlier that morning.

In the opening of the episode, we catch a glimpse of Piazza de’ Pitti, which I happened upon with Connie and Katie my first day in the city. It’s dominated by the formiddable Palazzo Pitti, a vast Renaissance palace that houses multiple museums, including the Palatine Gallery, the Gallery of Modern Art, and the Museum of Costume and Fashion. I didn’t get to any of these, but it remained quite the feat from the outside.

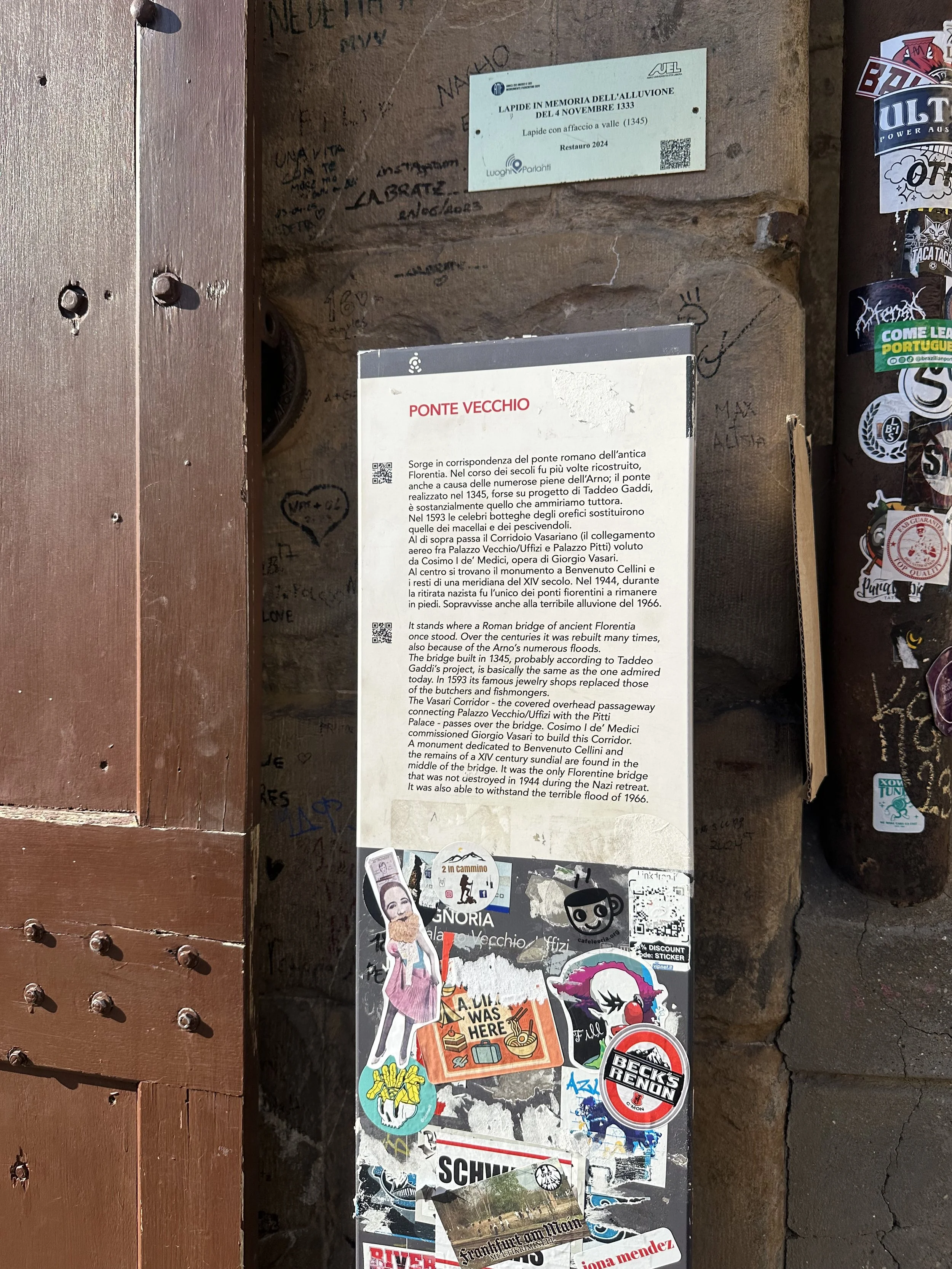

From the piazza, Harriet and Massimo must cross the Ponte Vecchio, the only bridge left intact during the occupation. I traversed the bridge more than a few times during my short stay in Florence, and each time, there were new shops to explore, more people to watch, and more bustle and energy than the time before. The Ponte Vecchio was one of my favorite landmarks in all of Italy. The banner for this page is taken there.

Piazza della Signoria and the Palazzo Vecchio are held firmly by the Nazis, their presence turning the civic heart of Florence into a backdrop of occupation. In one of Rossellini’s typical geographic ruptures, the pair suddenly appear in Rome, recognizable by the portico of “Fiammetta’s House” near Piazza Navona, where they knock on a doorway for refuge.

Their flight then suddenly takes them into the Boboli Gardens, normally a masterpiece of Renaissance landscaping but here transformed into a stage for war. In Paisan, Rossellini makes use of the Garden’s shaded walkways and wide clearings as corridors of escape, the hush of greenery contrasting violently with the chaos. The gentle slopes and feeling of being alone reminded me a lot of my time at the Baths of Caracalla in Rome: spaces that once carried the grandeur of history but now serve as rare moments of repose from the bustle outside.

The chase continues through the deserted Piazza San Giovanni where the Cathedral and Baptistery stand as ghostly silhouettes of cultural endurance, and even over the rooftops, suspended between the grandeur of the past and the violence of the present conflict. The chapter closes with a wounded man being carried into the wide clearing of Via Curtatone, and then in Via Solferino, with a partisan killed. It’s moments like these that punctuate the city’s topography with deeply intimate tragedy.

—