Rome

Upon my return to the States, I’ve been frequently asked to name a favorite Italian city. Perhaps I’m biased, since I spent the most time here, but my answer has always been Rome. It was the city I flew into and, in that sense, the first official stage of my journey. where this whole adventure began. Rome is a city of history, of endless movement, and—as I came to discover—unmistakable spirit and resilience. It is no wonder that Neorealist filmmakers turned to its streets for inspiration, given its role as a center of rebellion against the Nazis and other Fascist collaborators during the occupation.

The village of Attigliano, where I was staying at the time, lies about 58 minutes north of Rome by train. That made it surprisingly easy to go down for just the day. In total, I made five day trips to the capital, in addition to one overnight stay at a hostel downtown.

On my first trip, I had the brilliant idea of taking the 6:05 train. At that hour, there are no direct routes to Roma Termini, so I had to take a bus to the nearby city of Orte. I don’t think it’s a stretch to say I was the only person on that bus not headed to work. I was something of an intruder among what felt like a close circle of men and women on their sunrise commute. I couldn’t really follow their conversations, but I was captivated by their liveliness and enthusiasm. The sun had barely risen, yet their energy was nothing if not indicative of my destination.

Rome in June. The word that comes to mind is chaos. It’s loud, overflowing with people, and the heat is nearly unbearable. But at seven in the morning, the pandemonium is yet to begin. The air is still cool; the city streets are relatively quiet, save for a few residents hanging laundry from their windows and delivery trucks being hastily loaded. As the city slowly awakened, there was no better place to witness “life as lived” than in Rome’s Pigneto neighborhood, which is located just east of the Colosseum. The working-class neighborhood is divided into three sections, each with its own architectural variety, alternative shops, and street art lining nearly every block. Industrial Pigneto had clearly been neglected for a long time, and I understand why some say walking its streets doesn’t feel like walking through Rome at all. It was a unique introduction to the city, considering its atmosphere is so drastically different from that of the tourist centers. I appreciated the chance to see another side of Rome.

—

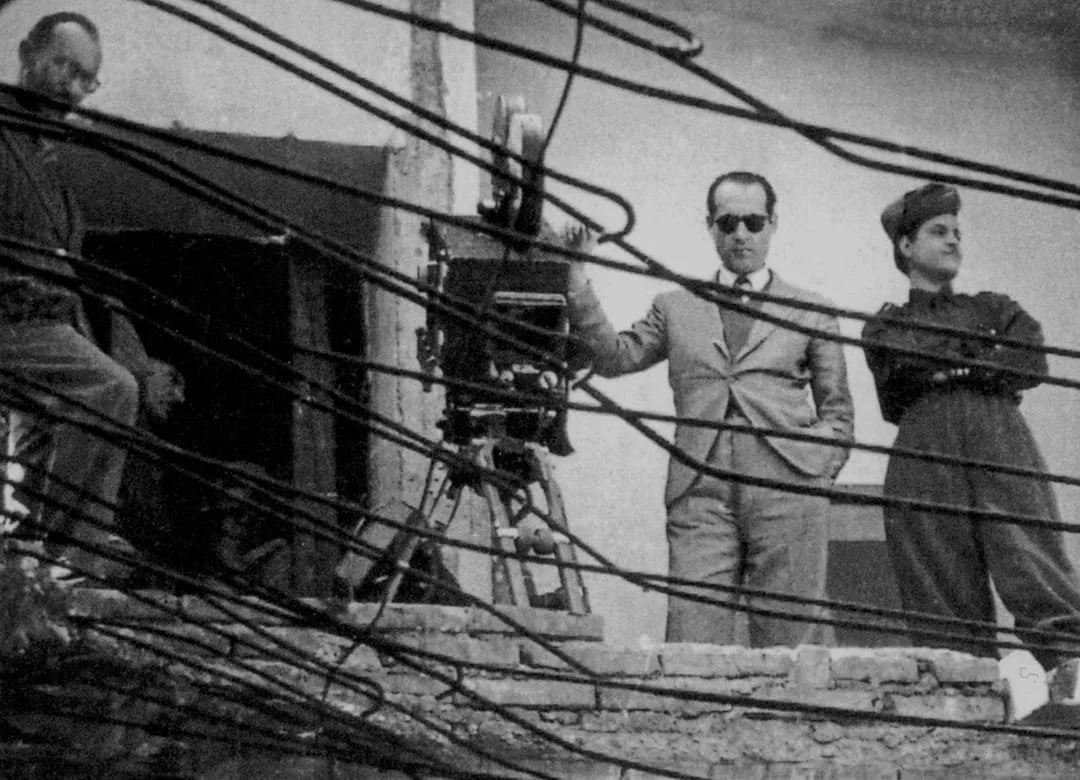

By 1944, Mussolini’s prized Cinecittà had been torn down, loaded onto trucks, and shipped to Nazi Germany. Under the allies, the complex was converted into barracks and later became a refugee camp. During the post-war era, getting film productions off the ground was nearly impossible, and filmmakers were made to get creative. Money and equipment were scarce, but professional actors were scarcer. It was Rome-native Roberto Rossellini who responded to these constraints by casting ordinary civilians as movie stars, often incorporating their own experiences into his scripts. To save on film-sets, he directed on site, even pre-Liberation, where he was forced to move houses nightly on account of routine searches by the Gestapo. Rossellini shaped the gritty aesthetic we know today—an aesthetic born as much from necessity as it was from vision. I do believe Pigneto became one of his most iconic backdrops; after all, Via Fortebraccio itself once sheltered Allied prisoners and endures as a powerful symbol of resistance.

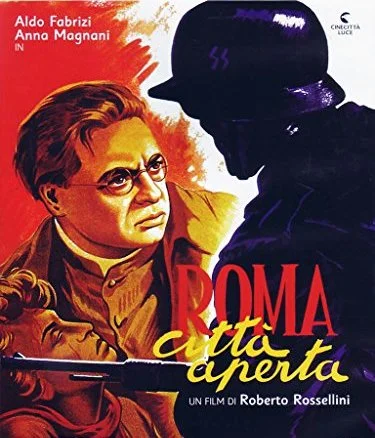

There are multiple Neorealist films that use Pigneto, including two of Vittorio De Sica’s other celebrated works, Il Tetto and Accattone. Both are remarkable and deeply influential, but the films I chose to explore in greater depth are Ladri di Biciclette (Bicycle Thieves) and Roma, Città Aperta (Rome, Open City). These two staples of the canon were created by Neorealism’s most prominent filmmakers, De Sica and Rossellini, respectively. Beyond Pigneto, I also visited numerous locations scattered across the city—some famous, others nearly forgotten—to enrich my studies. I’ll begin with Bicycle Thieves, as it was one of the first films that truly stayed with me.

“My father described himself as a seamstress sewing Italy’s torn fabric back together again. His aim was to make ‘un film utile’, reminding the world how Italians had also fought and died resisting Nazi Occupation.”

—Renzo Rossellini on his father, Roberto Rosselini

—

This shot on the right is actually one of my favorites. I can so vividly picture little Bruno darting through the shadowy alleys in hopeless pursuit.

After the war, much of Italy’s infrastructure was destroyed, especially in the northern region. Rome and Vatican City, however, also suffered heavily from a series of Allied bombing raids between 1943 and 1944. The U.S. targeted steel factories in the San Lorenzo district, but inevitably there was collateral damage: residential apartment blocks were leveled, and even the Papal Basilica was struck. Reconstruction would take years, and in the meantime Neorealist filmmakers captured an Italy still visibly scarred by the devastation of war. This backdrop cemented the spirit of struggle so clearly conveyed through De Sica’s characters and story.

All things considered, the preservation of many of these buildings and structures is remarkable. The historic Ponte Palatino, for instance, survived. It’s where I took the photo to the right. Spanning the Tiber, the bridge connects the Trastevere neighborhood (home to Porta Portese) with the Rione Ripa. In Bicycle Thieves, Antonio and Bruno cross the Ponte Palatino in pursuit of an old man they suspect of being the thief. He claims ignorance, but they follow him toward the city center, eventually arriving at the church of Santi Nereo e Achilleo, next to the Baths of Caracalla.

Antonio and Bruno’s chase carries them through a number of other prominent areas of the city, many of which I only came to recognize upon rewatching the film (e.g. Piazza Vittorio). The epilogue, however, unfolds on Via Flaminia, near the Stadio Nazionale, which is crowded with fans after a Sunday football match. The stadium—later renamed Stadio Torino in honor of the victims of the Superga air disaster—was demolished in 1957 to make way for the Stadio Flaminio, built in preparation for the 1960 Olympic Games.

In a final act of desperation, Antonio attempts to steal a bicycle himself. The effort is clumsy, and he is quickly caught and humiliated in front of his son. Yet the bicycle’s owner, moved by the sight of Bruno in tears, decides to show mercy, choosing not to press charges. In the film’s closing sequence, Antonio and Bruno walk up Via Flaminia, hand in hand, toward an uncertain future, swallowed by the indifference of the Eternal City. The moment is profoundly solemn, and I think this final shot is what makes Bicycle Thieves linger. There is no uplift, and certainly no justice.

But through war and suffering, life goes on. More than any city in the world, Rome has maintained a toughness and quiet resiliency that is difficult to replicate. As Antonio and Bruno dissolve back into the anonymous crowd, it is tempting to read this cyclical progression as pretty Kafkaesque—unresolved and purely cynical. But the heartbreak does not have to feel bleak. In its own way, the ending reminds us that our challenges have been faced by those before us and will be faced by those who come after us. There is strange comfort in the universality of tragedy.

Bicycle Thieves is, ultimately, a nuanced story about humanity—about crime, loss, and the desperation born out of poverty. De Sica handles this material with grace, refusing to sensationalize hardship or lapse into didacticism. Instead, he allows the story to unfold with profound simplicity.

—

Produzioni De Sica

Porta Portese is one of the first places Antonio and Bruno search for the stolen bicycle. Today, the flea market is just as lively as it appears on screen. The piazza overflows with an eclectic mix of trinkets: t-shirts, paper fans, coastal jewelry. The atmosphere is frantic, almost chaotic, and the film captures this energy perfectly.

Located in Trastevere, the market has become something of a Sunday ritual for Romans. It opened shortly after World War II and, for the past 80 years, has given people a place to barter and sell all manner of goods. To me, Porta Portese felt like one of the city’s first steps toward reconstruction, as it helped restore the sense of human connection Rome had been deprived of during the war.

It’s also just great fun. I bought my very first souvenir here: an “Italia” t-shirt for a mere €5.

These baths were one of many ancient ruins I explored, but were unique in that they were practically empty. The baths were enjoyed by the Romans from around 216 A.D. to 537 A.D, and they even had some of the tile still intact, which was astonishing. What’s interesting is that they’re actually located in one of Rome’s working class areas, despite containing quite the assortment of lavish sculptures and architectures.

I vistited right after my chaotic tour of the Colosseum and Palantine Hill, making the Terme di Caracalla a lovely change of pace. The towering walls cast broad stretches of shade across the grounds, offering repose from the relentless Italian heat. Wandering through the ruins was quiet and serene, the vast space carrying an almost monastic energy despite their scale.

Though I’ve always had a hard time with the concept of communal baths; even CMC’s communal bathrooms were a bit of an adjustment.

Bicycle Thieves (1948) stars Lamberto Maggiorani as the unemployed Antonio Ricci. Amid widespread poverty in Rome, Antonio is elated to land work pasting up advertisements around the city. But his job comes with one condition: he must own a bicycle to get him to and from work. After pawning some of her bed linens, his wife, Maria, comes up with the extra cash to pay for the bicycle. However, rather predictably, the Riccis’ fortune is short-lived. On Antonio’s first day of work, his bicycle is stolen. The thief vanishes into the crowded streets, leading Antonio and his young son, Bruno, on a futile chase to recover it.

In the opening half hour, the film’s socio-political terms are made explicit: Antonio and Bruno first consult the city police, only to be met with bureaucratic indifference. Too preoccupied with the lack of running water in their own apartments, their neighbors won’t help them either. Antonio and Bruno are left to continue their search alone, adrift in an unempathetic city stretched thin by poverty. Bicycle Thieves is a story of an individual hardship made all the more crushing by the apathy of the collective. The film is compelling, but above all, melancholic. Yet it is not a melodrama. Without wringing out tragedy, De Sica offers us an honest window into the demoralized psyche and pervasive isolation of a defeated nation.

Over the course of Antonio’s search, audiences are steered away from Rome’s elegant ruins and crowded museums. Instead, the camera leads us through the city’s rougher underbelly, which in 1948, was painfully visible. Standing in some of these same locations myself gave me a more visceral sense of the spaces and atmospheres that make the film so enduringly powerful.

It’s a dizzying, spiralling descent into desperation. Truly masterful, and in keeping with the somber yet deeply human quality of all Neorealist cinema.

Produzioni Rossellini

Piazza di Popolo (6/21/25)

Roman Forum & Palatine Hill (6/20/25)

The director Otto Preminger said, “Cinema history divides into two epochs: Before and after Roma, Città Aperta.”

This is my favorite film from Rossellini’s war trilogy and from the Neorealist canon at large. Released in 1945, right on the heels of Rome’s liberation, Rome, Open City brought the camera out into the rubbled streets of the city and captured not merely what had happened, but what was still happening. It was an incredibly bold thing to do. World War II changed the way people saw the world, and Rossellini used cinema as a way to understand it. He was one of the first directors to use art to examine humanity at its most horrific, and that sense of urgency pulses through the film and hooked me from the opening scenes. I do believe it is more melodramatic than Bicycle Thieves, but it’s also tightly paced and incredibly gripping. A lot of my favorite movies—war-time and not—owe Rome, Open City a clear homage.

The story begins in Nazi-occupied Rome in 1944. Resistance fighters are hunted relentlessly by German forces, and the city lives under constant fear of raids and arrests. Pina, a working-class woman played by Anna Magnani, is engaged to Francesco (Francesco Grandjacquet), a printer and committed communist. Pina helps shelter fighters, spreads pamphlets, and organizes underground activity for the Resistance, all while caring for her young son, Marcello. Don Pietro, the parish priest played by Aldo Fabrizi, secretly aids the fighters despite the moral ambiguity of stepping beyond his role in the Church. The film opens with Resistance leader Giorgio Manfredi (Marcello Pagliero) being forced into hiding while on the run from the Gestapo.

In comparison to Bicycle Thieves, Rome, Open City opens its story to the whole of Roman resistance. Whereas De Sica narrows the lens to the struggles of one impoverished family, Rossellini portrays the suffering of an entire city under Fascist occupation, painting a broader picture that includes the Roman middle class, equally exasperated and disillusioned by the state of their city.

A lot of Rome, Open City takes place indoors, in apartments, parish rooms, and interrogation chambers, where characters are forced into hiding from the Nazis. Unlike Bicycle Thieves, which unfolds almost entirely in the open streets of Rome, this meant I couldn’t trace as many distinct outdoor locations tied directly to the film. Instead, much of my engagement with it came through Rome’s World War II history at large.

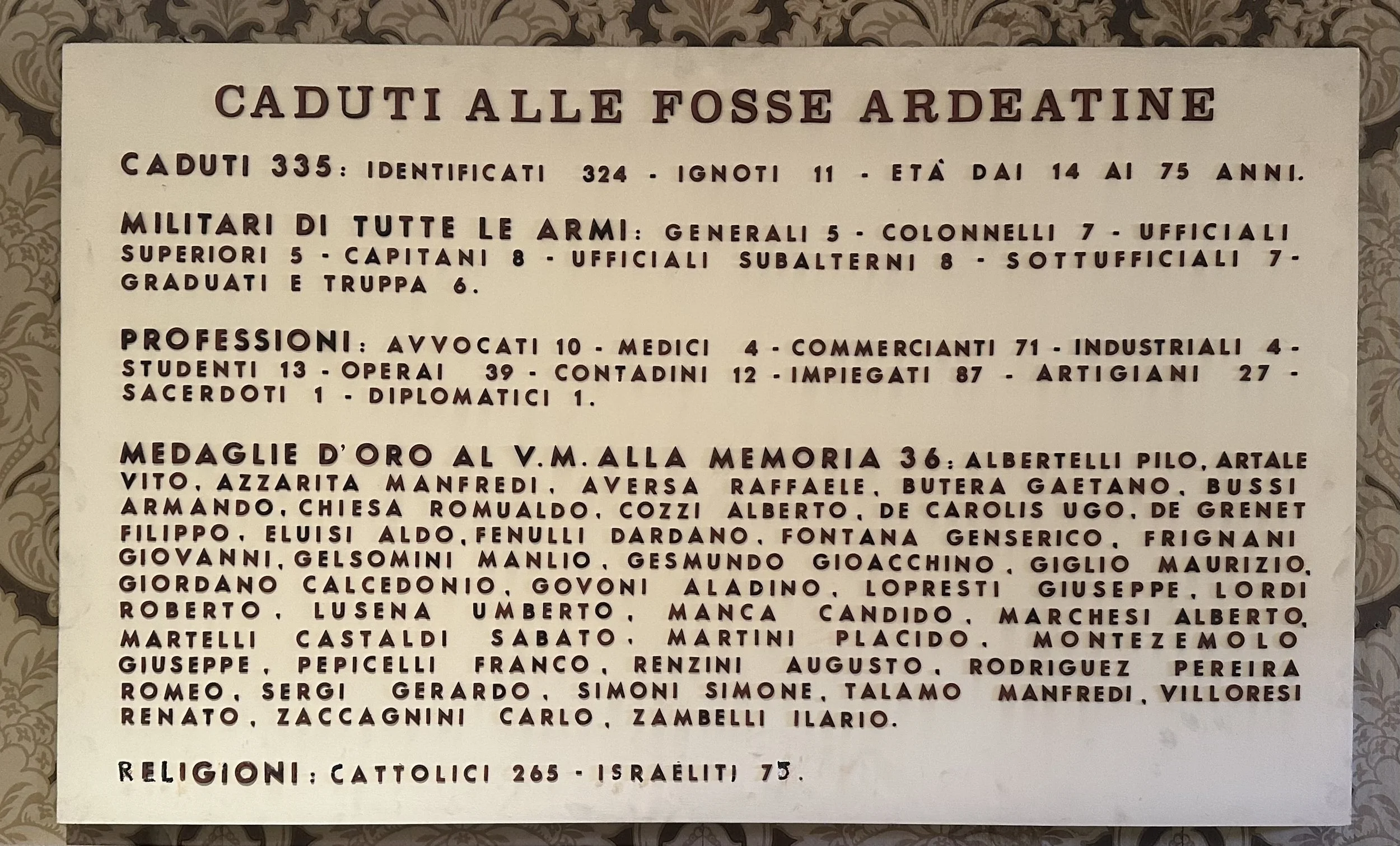

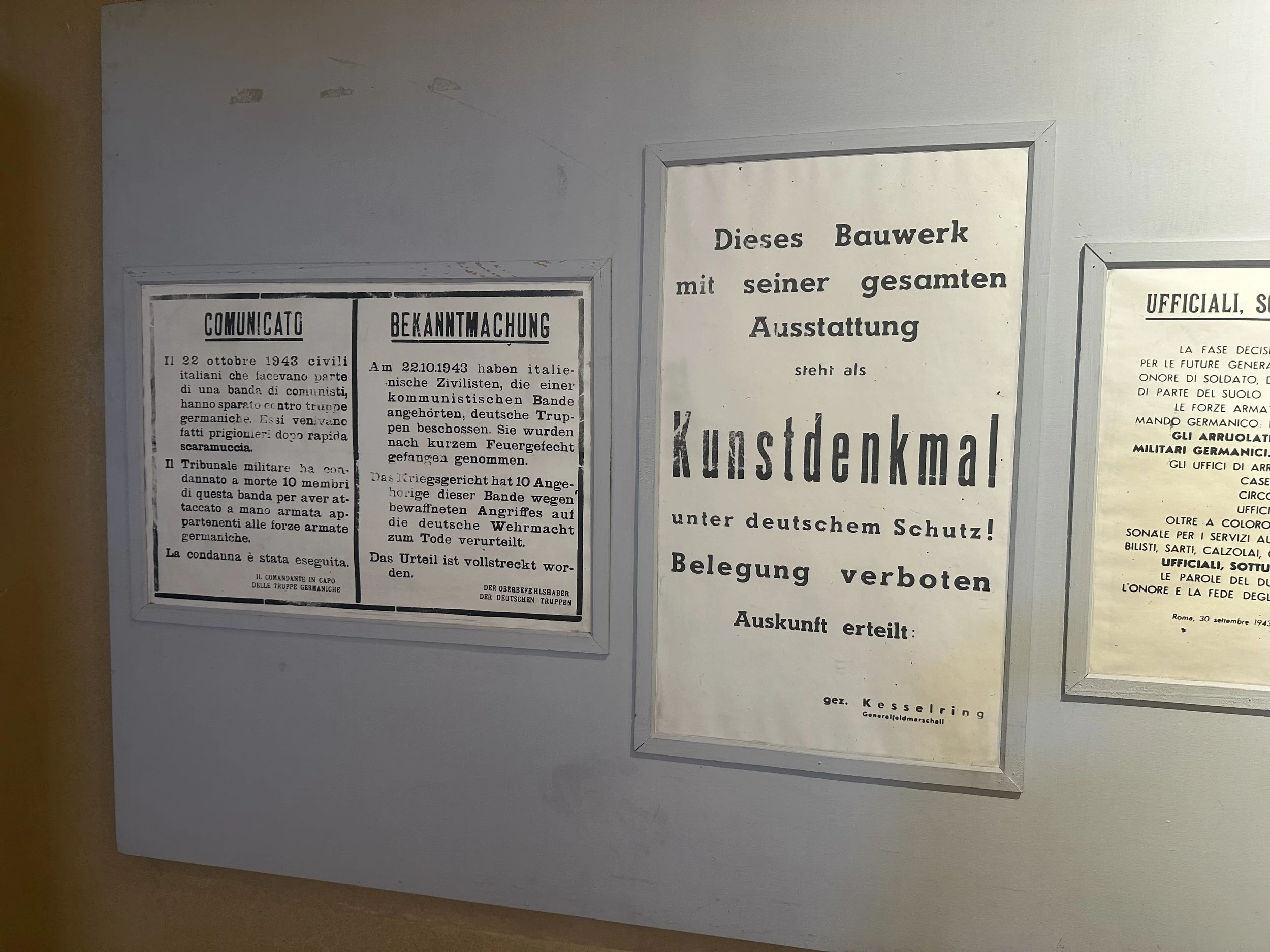

I made it to the Museo Storico della Liberazione, located on Via Tasso in the center of Rome near the Basilica of St. John Lateran. The building itself once served as the SS headquarters and is the very place where Rossellini set the torture of Giorgio Manfredi in Rome, Open City. The museum feels old-fashioned, more like an archive than a polished institution, but I think that allowed a lot of the history to speak for itself. The place was almost completely deserted (I don’t think many people know about it), so just walking through the stairwell and hallways was incredibly eerie. In a city as busy and loud as Rome, being alone in those rooms made it feel less like a museum and more like being left face-to-face with the city’s tragic history.

The preserved prison cells were the most powerful part for me. Their doors, windows, and walls have been left just as they were in the 1940s, and you can still see the messages carved by prisoners who waited there: names, dates, prayers, final words. Some of the graffiti was in English, etched by captured British soldiers, which really struck me. It was a stark reminder that what happened here wasn’t just Rome’s tragedy but part of a larger war that touched the lives of so many beyond Italy. In those cramped rooms, you feel so close to the people who had lived out their last days right where you’re standing, and it was really moving. I’ve included photos of a few messages below.

The next floor takes a turn. There are cases upon cases of Nazi propaganda—pamphlets, decrees, ration orders, anti-Jewish laws—all lined up behind glass. Some of it is in Italian, but a lot is in German. Nearby, there was a section dedicated to Don Giuseppe Morosini, the parish priest executed by the Nazis who, along with Don Pietro Pappagallo, directly inspired Rossellini’s Don Pietro. Seeing his photograph and reading about his capture and death gave that final scene of the film a heavier weight. However, my favorite exhibition on this floor was a room devoted to the biographies of women in the Resistance. Reading their stories gave me a fuller picture of the movement and the risks that ordinary people like Pina were willing to take.

"I am a Catholic priest. I believe that those who fight for justice and truth walk in the path of God and the paths of God are infinite."

These are the words of Don Pietro, the film’s moral center. Although his parish church is technically fictional, it remains a central location in the story. Scholars trace the exterior shots to resemble the Church of Sant’Elena on the outskirts of the city. I didn’t make it that far, but I stumbled into a humble neighborhood church in San Lorenzo that reminded me so much of Rossellini’s. It was modest, lightly unadorned, and the kind of place you’d imagine someone like Don Pietro quietly working in the background.

In the film, the church is where he shelters resistance fighters, conceals weapons, and even arranges clandestine meetings. What’s powerful is how Rossellini chose not to set these moments in the grandeur of St. Peter’s or some monumental basilica, but in a small parish space where faith and resistance intersected in everyday ways.

The theme of religion affected me in many interesting ways. I will revisit this later.

A Further Gallery of Rome

This section is a collection of landmarks and postcard views of Italy.

Monument to Victor Emmanuel II (6/15/25)

Spanish Steps (6/24/25)

Mouth of Truth (6/20/25)

Rafael’s School of Athens in the Vatican (6/20/25)

Pantheon (6/15/25)

St. Peter’s Basillica (6/24/25)

After leaving the museum, I wandered through nearby Celio, the Roman neighborhood where parts of Open City were filmed. It’s quieter and more working-class than the tourist-heavy parts of the city. I definitely stood out, and a few people gave me curious looks, probably wondering what I was doing there with a camera. Still, I always found the people in these neighborhoods to mostly have kind, open faces.

Here’s a memory: it was around midday, and the primary school next door must have let the children out for lunch. The sound of their laughter and shouts filled the streets, and for some reason it really hit me. Maybe it was because youth is such a significant theme in the film—Marcello and the parish boys taking up the fight after Don Pietro’s execution—but it was also the universal quality of it. Kids playing kickball in Celio aren’t much different from the kids at my summer camp back home, or from me when I was their age.

Another thing that struck me was the amount of activism in the area, which I suppose makes sense given the nature of the cinema I’m studying. Posters and graffiti called for justice in Gaza and other causes that stretch far beyond Italy. This neighborhood has long carried a spirit of resistance (the bullet holes on this old building mark the 1944 Via Rasella attack when partisans ambushed Nazi police), and seeing people advocate for the same liberties today tied the past to the present. The fight against oppression isn’t bound to one country or one time but continues, and Rome still feels alive with it.

Finally, I made my way to Via Raimondo Montecuccoli, the street where Pina is gunned down by the Gestapo. What struck me most was how lived-in the place still feels—neighbors gathered around café tables, teenagers sharing cigarettes outside the metro station, kids rushing home from school. Nothing about it announces “film history,” yet her death is one of the most famous ever captured on screen.

In the film, Pina has just seen her husband-to-be, Francesco, dragged away by German troops. She runs after the truck, screaming his name, before she is ruthlessly gunned down in the street. I loved Magnani’s performance in Open City—she anchors the entire first act, bringing such raw, naturalistic energy to the role that her sudden removal feels like a gut punch. Her son Marcello rushing to her body remains one of the most heartbreaking images in cinema.

I’ve already mentioned how much of Open City unfolds indoors, which made it difficult to retrace those steps the way I could with other films. I didn’t physically visit the execution sites of either of the following characters, but still, I wanted to say a few words.

In short, by the end of Open City, pretty much everyone is dead. Giorgio Manfredi, the Resistance leader, is betrayed by his girlfriend and tortured to death by Major Bergmann and the Gestapo. Don Pietro, the parish priest who risked everything to aid the partisans, is forced to watch Manfredi’s suffering before being taken to Forte Bravetta and executed by firing squad.

For audiences in 2025, I assume Manfredi’s interrogation was pretty shocking. To my understanding, mainstream media up to that point (think Hollywood films like Casablanca or Sahara) had certainly painted the Nazis as villains, but usually through threats, harsh interrogations, or dramatic arrests. There were no prolonged torture sequences shown in such raw detail. Either the violence was softened for audiences, or it stayed entirely offscreen. I’m not 100% sure Rossellini was the very first to show it, but the authenticity of this sequence jumped out at me in particular. Another thing that feels revolutionary is Major Bergmann’s character. He’s polite, measured, disturbingly charming. I recently rewatched Christoph Waltz in Inglourious Basterds, and Bergmann struck me as his direct descendant: the Nazi who inflicts violence as if it were nothing more than daily routine. Rossellini gave us the blueprint for one of cinema’s most chilling kinds of evil.

Next comes Don Pietro’s dawn execution. Inspired by real priests—Don Giuseppe Morosini and Don Pietro Pappagallo—he is taken to an isolated clearing and left before his persecutors. The soldiers hesitate, as if Rossellini is offering them one last chance at redemption, but the shot comes anyway. His death might have gone unnoticed, just another casualty in occupied Rome, if not for the parish boys who suddenly appear behind the fence, whistling in solidarity. His killing becomes a ‘death with spectators,’ and Rossellini makes us witnesses too. Yet the boys at the fence suggest his legacy will endure, reminding us that faith itself is a form of resistance. Just as De Sica assures us life goes on at the end of Bicycle Thieves, Rossellini insists Rome is resilient, and with the morning sun will rise again.

—

Colosseum (6/20/25)

Trevi Fountain (6/20/25)

Palazzo Venezia (6/15/25)

Café Canova, Fellini’s Spot! (6/21/25)

… & sunset views from the city center (8:24 pm)

Mussolini’s Balcony (6/15/25)

Fellini’s apartment @ Via Margutta, 110

The Interior

A Disclaimer on Hollywood and Neorealism

In all my talk of Neorealism, I want to clarify that it is not my intention to dismiss its classical Hollywood contemporaries. It’s true, I tend to warn against films that function solely as outlets of escapism, but that doesn’t mean these “dream machine” movies aren’t delightful in their own right. After all, who wouldn’t want to watch Audrey Hepburn frolicking around Rome in a striped neckerchief every once in a while?

What comes to mind are films like Roman Holiday, La Dolce Vita, and Light in the Piazza—all romantic, fairy-tale adventures that stood in stark contrast to the new direction Italian cinema had taken after WWII. While directors like De Sica and Rossellini brought their cameras into the ruins, American filmmakers chose to portray Italy at its very finest, even if it meant ignoring reality. Audiences clung to that bit of bliss movies gave them, a relief from a world that had just been struck by unprecedented evil.

From the bottom of my heart, I don’t think there’s anything inherently wrong with returning to these kinds of films. But it has to be in moderation, and always with the understanding that they are fantasy. The fakery didn’t bother Americans back then, and I’m not saying it should bother us now, but we must recognize that cinema has the courage to tell us fuller stories, and we ought to be brave enough to face it.

Just like Princess Ann, we all deserve a vacation, but we also all return to reality at some point. Roman Holiday shouldn’t feel like a guilty pleasure, because I think these kinds of movies are necessary to make processing the harsher truths of history a little easier. That being said, I’d like to end with this: escapism may offer us comfort, but realism offers us understanding. Movie-lovers should appreciate both.

—

Roman Holiday (1953)

The Yellow Rolls-Royce (1964)

8 1/2 (1963)