The Film Movement that Bore Witness to War-Torn Italy

"I try to capture reality, nothing else." - Roberto Rossellini

Before we begin, it’s only fair to provide you with some brief historical background, along with an overview of the movement’s most defining features.

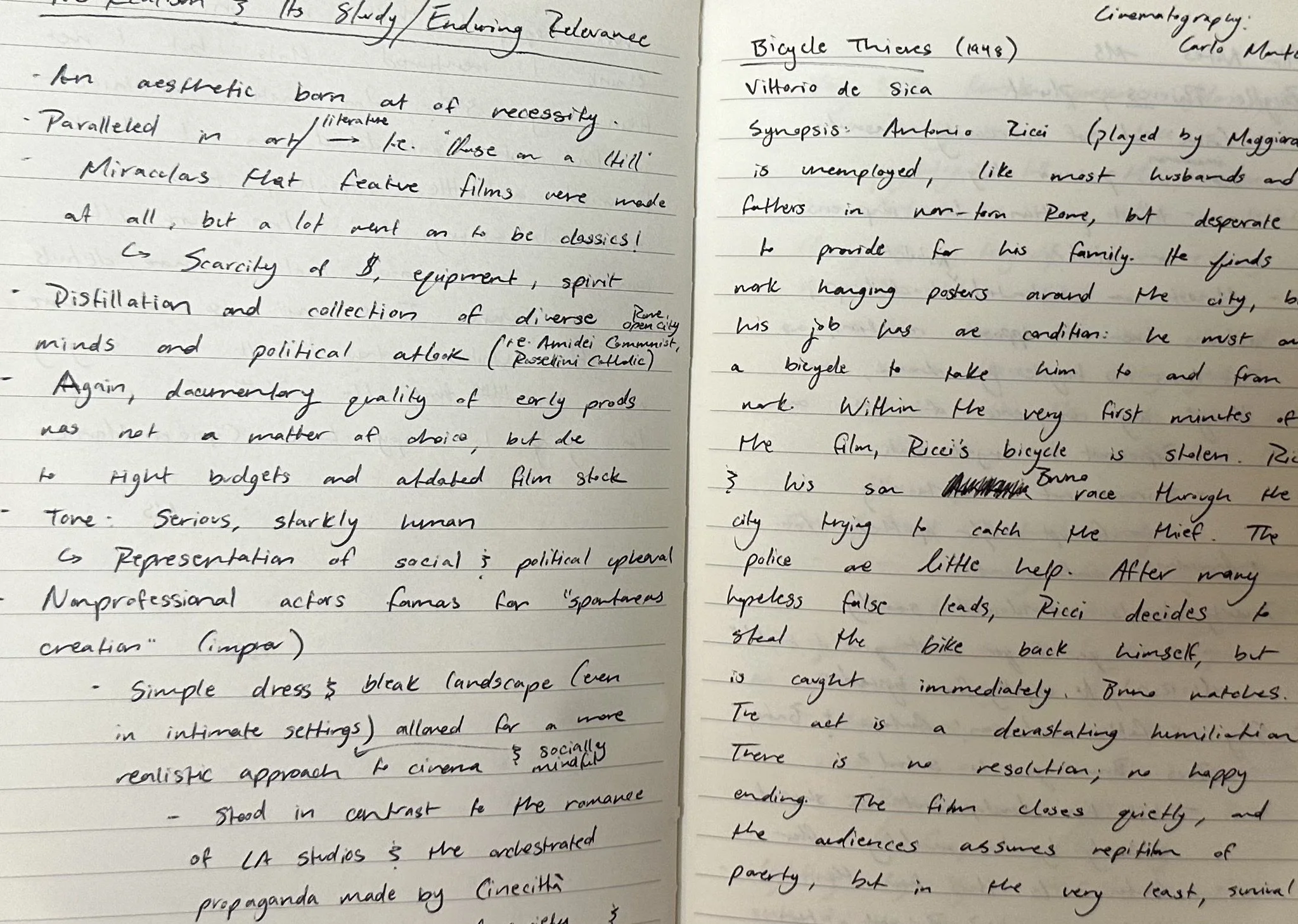

In the eyes of Benito Mussolini, “il cinema è l'arma più forte,” which translates roughly to “cinema is the strongest weapon.” In 1937, he founded Cinecittà, a sprawling studio complex on the southern edge of Rome. Under his dictatorship, Mussolini nationalized filmmaking and used the studio as a political tool to glorify Italian fascism. The movies produced at Cinecittà were typically high-society romances or swank productions set in grand hotels and nightclubs. They belonged to what became known as the “white telephone” genre (most Italians owned ordinary black telephones), which promoted a glamorous, idealized vision of life under the regime, where protagonists always found neat resolutions to their shallow dilemmas. Other films celebrated the triumphs of Rome’s past, while still others were simply American imports. The screen hardly resembled the people’s own lives.

Mussolini sought to dictate public imagination, and his propaganda stifled the birth of a truly Italian film movement. Yet even under his regime, a desire for realism was brewing. In fact, Cinecittà ended up nurturing some of Neorealism’s most important figures. Vittorio De Sica, for one, began his career as an actor in Mussolini’s film industry before later emerging as one of the movement’s leading directors. Free from fascist censorship after the war, he and others could finally portray Italy as it really was, with a critical eye toward the social problems permeating the nation.

Shortly after the Allies advanced into Rome, Cinecittà shut down. The Neorealists seized the opportunity to challenge the conventions associated with pre-war cinema. However, with no studios, film crews had no choice but to look into new means of production. They turned to the anxious streets of Rome, holding up a mirror to the face of their struggling society. This they did to great effect.

Ideology & Style

Although Neorealism is a distinctly cinematic creation, it was informed by an anti-Fascist philosophy; many Italians, after all, felt it was finally putting images to the ideas of the Resistance. Here are the movement’s ideological characteristics:

A new democratic spirit that affirmed the dignity and worth of ordinary people

A refusal to reduce human lives to simple moral judgments

An unflinching engagement with Italy’s Fascist past and the devastation left in the aftermath of dictatorship and the war

A synthesis of Christian and Marxist humanism, combining moral compassion with social critique

An insistence on grounding art in lived emotion rather than abstract theory

Neorealism also embraced revolutionary artistic tendencies, seeking to show life as it unfolded in real time and resisting the temptation to manipulate through editing. Here are some of those stylistic elements:

Stories built on loose, episodic structures rather than fixed plots

A visual style modeled on documentary realism

Filming on real locations, most often exterior streets and landscapes

Casting nonprofessional actors, often in central roles

Dialogue that emulates everyday, conversational speech

Editing, camerawork, and lighting kept simple and naturalistic

While it is true that much of the Neorealist aesthetic arose from circumstance and economic constraints, many of the choices directors made were meant to defy Mussolini’s film industry. Their portraits of a desolate, poverty-stricken country outraged contemporary politicians who were eager to present Italy as a nation on the road to democracy and prosperity. De Sica in particular faced sharp criticism from Giulio Andreotti, a Christian Democratic statesman who would later become one of Italy’s most powerful prime ministers. He accused him of “washing Italy’s dirty laundry in public.”

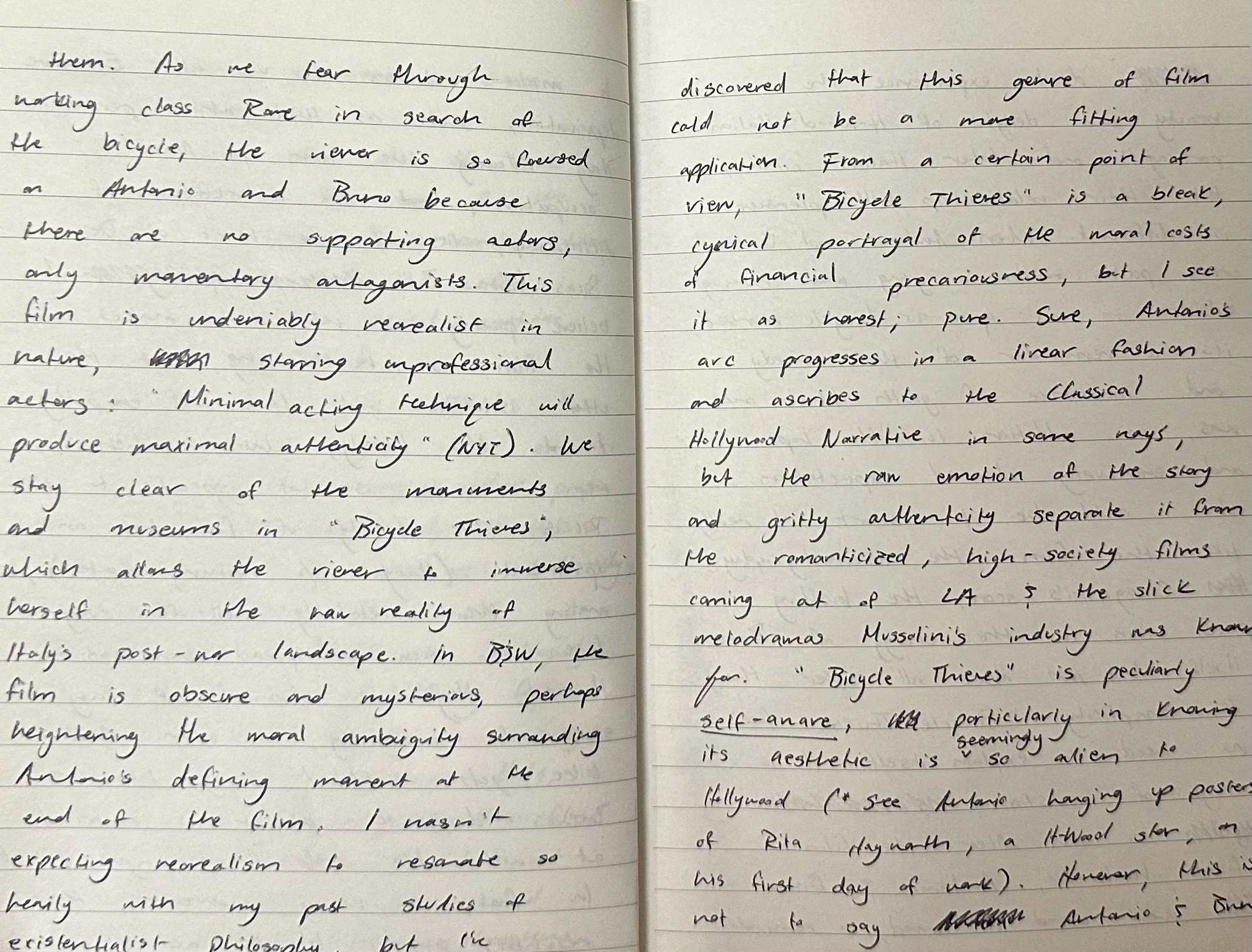

Perhaps the most original characteristic of the new Italian realism in film was the faith directors placed in nonprofessional actors. They believed that minimal acting technique yielded maximal authenticity. Some directors even invited their actors to contribute directly to the script, while others relied almost entirely on the art of improvisation. They then positioned their characters within equally authentic environments, favoring the piazzas and courtyards where daily life unfolded free from intervention. In abandoning the controlled conditions of the studio, they surrendered much of their traditional authority over production. Cuts were unobtrusive, lighting was dictated by natural sources, and the background carried the unscripted noise and movement of the urban environment.

Even so, the legacy of Italian Neorealism lies less in the codification of a single style than in the articulation of a common aspiration. What bound the movement’s filmmakers together was not strict formal uniformity but a shared determination to confront Italy without preconceptions, and to forge a cinematic language that was at once more honest, more ethical, and yet no less poetic. In this sense, Neorealism was never a school in the traditional sense. It was instead a collective sensibility, born out of a specific historical moment, that challenged both the aesthetic conventions of Fascist-era cinema and the commercial formulas of Hollywood.

The impact of this shift cannot be overstated. By turning the camera toward ordinary people and the realities of daily survival, Neorealism permanently altered the possibilities of narrative film. Its influence stretched far beyond Italy: the French New Wave absorbed its lessons in location shooting and improvisation (“guerrilla filmmaking”), while New Hollywood directors carried forward its commitment to authenticity. Even Quentin Tarantino, in his self-referential postmodern masterpiece Pulp Fiction (1994), drew upon this lineage, adopting nonlinear plot structures and centering complex, multifaceted antiheroes. Filmmakers across the globe—from Satyajit Ray in India to contemporary auteurs like the Dardenne brothers—continue to draw upon Neorealism’s aesthetic and moral principles. More than a style, it has became a touchstone for any filmmaker seeking an affinity between art and social reality.

Yet the legacy of Neorealism is also one of transformation. Some of its earliest practitioners, including Rossellini, De Sica, and Visconti, eventually moved away from its strict formulas as Italy itself evolved, while younger filmmakers carried its spirit forward in new directions. Among them was Federico Fellini, who began his career as a screenwriter and assistant under Rossellini before moving into directing within the Neorealist framework. Over time, however, he expanded its horizons, infusing his work with spirituality, dream, and metaphysical imagination. Fellini embodies the paradox of Neorealism’s endurance: although rooted in documentary-like immediacy, it opened the way for cinema that allowed directors to explore deeply personal evaluations of the human condition. For this reason, it is fitting that the last word on Neorealism should belong to Fellini.

—

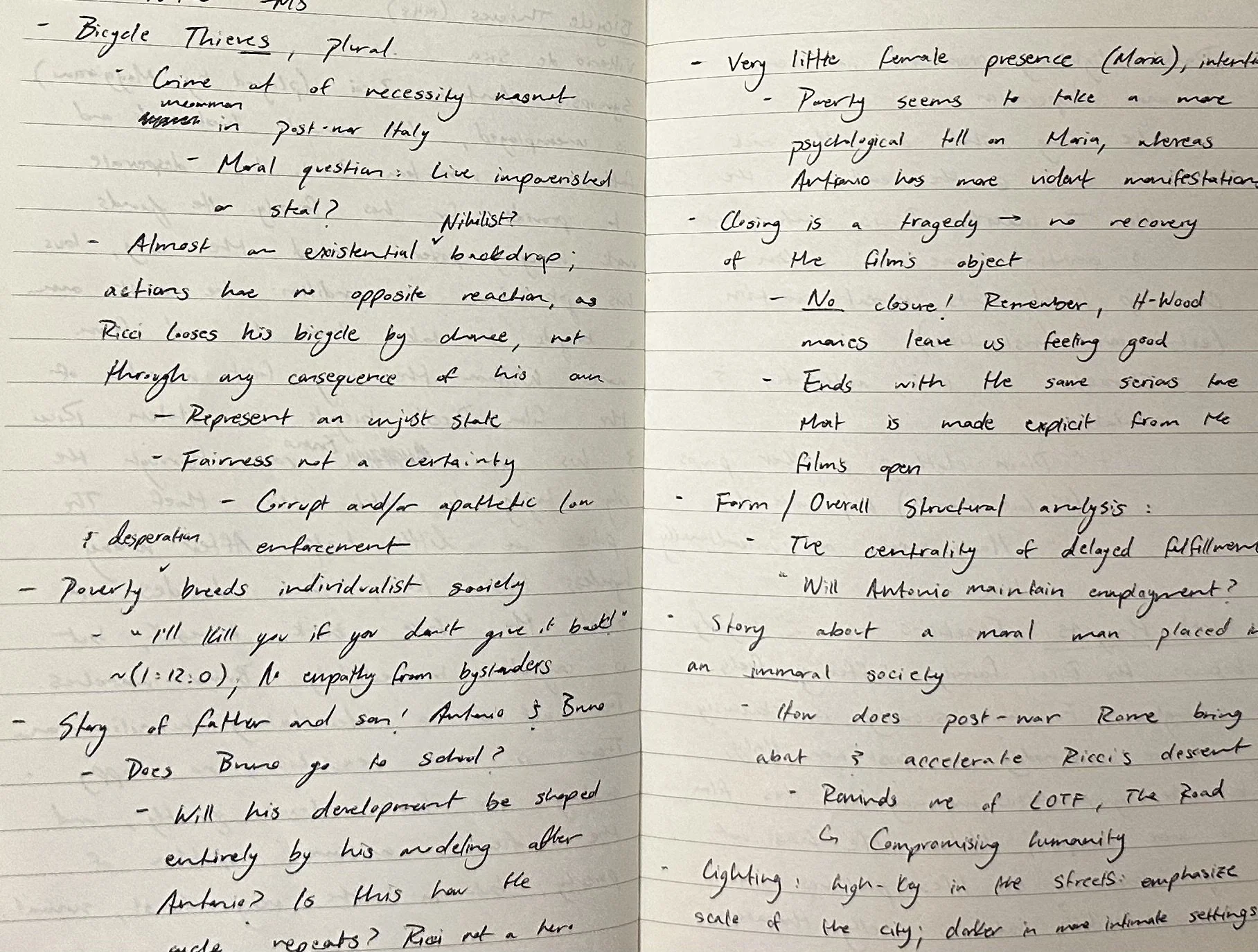

By the strict accounting of some critics, there are exactly seven films in the Neorealist canon: three apiece by Vittorio De Sica and Roberto Rossellini, and one by Luchino Visconti. These include Ossessione (1943), Rossellini’s Rome, Open City (1945), Paisan (1946), and Germany, Year Zero (1948), along with De Sica’s Shoeshine (1946), Bicycle Thieves (1948), and Umberto D. (1952). I watched all these and quite a few more, but the next tab over focuses on those whose filming locations I was able to explore in the most depth. Throughout my travels, I kept my analyses in a journal.